OMG Decisions!

This is a summary of a presentation I gave at the Content Strategy Barcelona Meetup on 20th November 2014 - a refresher for those who attended, and an appetizer for those who want to book me for this or similars presentations. If you’ve got a project that involves content strategy and people (most of them do, right?), give us a call in Hamburg or Barcelona.

(Again; keep in mind that this is a summary, not a full-fledged article. This is a first draft, written top-down, without editing or proof-reading, so don’t expect a detailed treatise on the matter. If you have any questions, drop me a note using the contact details at the end of this post.)

Part 1. OMG DECISIONS! – What makes them so hard?

Depending on which psychological study you’re reading, humans make between around 100 and 1.000 conscious decisions per day, and many, many, many more unconscious decisions. In CS projects, seemingly simple actions like adding a team member to a project or moving a deadline can lead to an explosion of the decision space which pretty much feels the same way as if your brain were replaced by a glob of spaghetti.

This can (and does) happen during content creation (e. g., which content are we going to create for whom, in which tone, with which tools?), in curation/publication (e. g., which channels are we going to use?), in HR (e. g., should we convince our client to move his employee A from X to Y?), and many other contexts.

My belief (and experience) is that when everyone takes care of his own decision strategies (which basically means taking care of oneself), the positive effects will be taken up systemically by teams and business units and eventually - I’m an optimistic guy - the whole organization.

Think about your last face-off with the menu at a restaurant. How did you decide what to eat? Most people will respond that they don’t know, and that’s perfectly alright - though it helps to be attentive to one’s own decision strategies in everyday situations because they shape our strategies in more “important” contexts.

(Aside: When going out with a group, you probably have experienced that guy or that girl who always says “Well, if you are having chicken, I must have beef” or “Tell me what you’re having so that I can order something else,” right? Keep them in mind when you’re at a business meeting and marvel at the Games People Play.)

The main issue people have with decisions is that they think they can plan the future. They are mistaken.

The main issue people have with decisions is that they think they can plan the future. They are mistaken.

The main issue people have with decisions is that they think they can plan the future. They are mistaken.

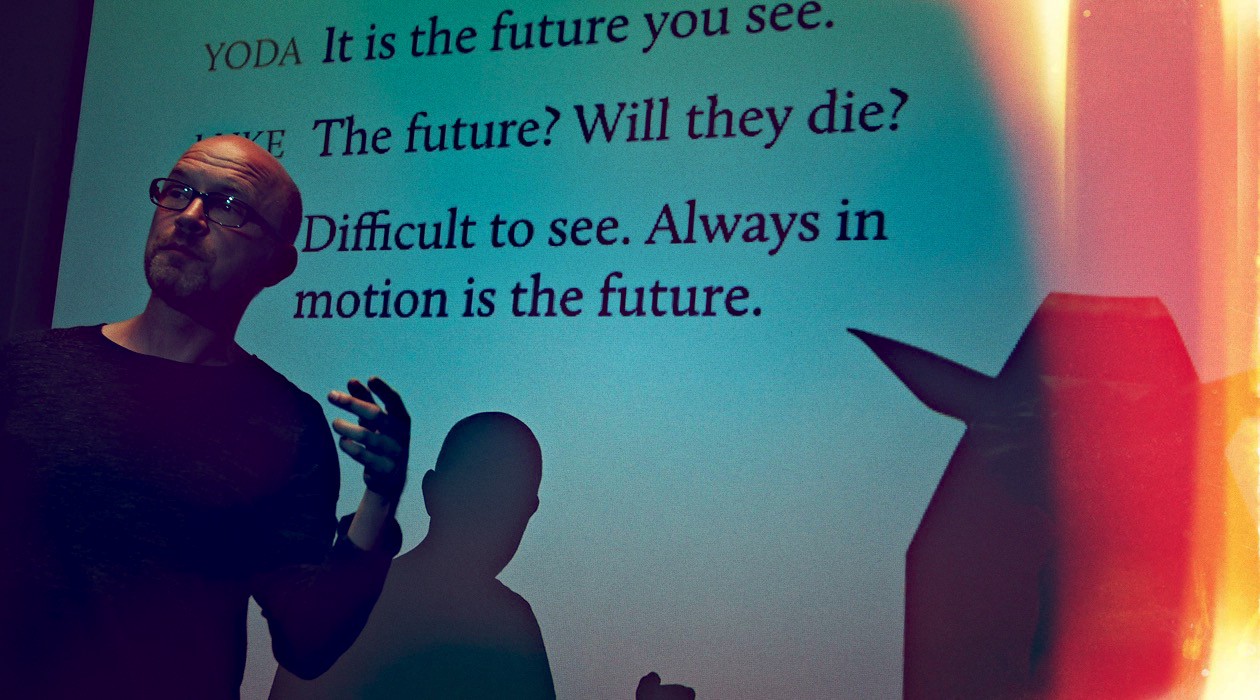

What? Yeah, I did repeat myself, just because it’s so important. Remember Yoda in The Empire Strikes Back? “Difficult to see. Always in motion is the future.” He made a massive understatement there. You can never know the outcome of a decision. You might be able to guess, but that’s it.

Also, hindsight is 20/20, which makes some people think that “if only we had decided B instead of A, we would have gotten a better result.” This is pure, crystal-clear bullshit, and a sign of massive hubris. Please, please, please don’t do this. Please.

Part 2. Making Smarter Decisions

SO, what can we do to make better decisions at an individual level? (Keep in mind we’re talking about individuals here; not teams. But if individuals learn to make better decisions, the team will as well.) There are at least four strategies:

First, think even more. This usually does not work as expected, so I didn’t spend too much time discussing this in the talk.

Second, trust randomness. Throw some dice, or a coin. Several experiments with monkeys’ random investment decisions seem to lead to the conclusion that randomness can be your friend. Also, if you’re stuck at a decision and (as we showed) cannot see the future anyway, throwing a coin can help you get unstuck. It also helps reducing complex decisions to a set of simpler decisions which can be helpful in and of itself.

Third, go slo-mo. (Cue still image of Neo stopping bullets mid-air in Matrix.) When you’re making a decision, slooooow down your thought and emotional processes to learn more about your individual decision strategy, then optimize. (I talked much about this in the lecture, but alas, this post is too small to contain everything.)

Fourth, act fast. This does not mean to break things fast, or to fail fast. You do not succeed by failing, you succeed by succeeding. The usual way of explaining decisions is “killing the alternatives” (en. decision via French from Latin (de)caedere, i. e. cut or kill.) The German word for decision is Entscheidung, and it has an additional meaning: It can be etymologically traced to pulling the sword out of its sheath (ent=out or away, Scheide=sheath), i. e. get into action. If you kill something or someone is not important - what’s important is to get going, and you could use a sword to cut up a delicious pineapple, right?

The Seven Breaths, my favorite strategy, as explained in [Hagakure]:

In the words of the ancients, one should make his decisions within the space of seven breaths. Lord Takanobu said, “If discrimination is long, it will spoil.” Lord Naoshige said, “When matters are done leisurely, seven out of ten will turn out badly. A warrior is a person who does things quickly.”

By all means, try this, even if it sounds like ninja woo-woo. TRY IT. Really, do. When faced with a decision, lay out the options: A, B and C. Then start breathing, and count ONE. The beautiful thing is that you cannot stop once you’ve started, so you’re going TWO … THREE … and as you probably don’t want to hold your breath indefinitely, you will arrive at SEVEN. Watch your mind race while you’re counting. (It’s so so beautiful that I always get carried away talking about this, so be glad you’re reading just the summary here.)

Part 3. Learning to do the Crawl

OK, so you know some new strategies that can help you make better decisions … how are you supposed to actually learn them?

There’s one beautiful learning model developed by (most probably) Noel Burch, and you’ve probably heard about it:

- First, there is the stage of unconscious incompetence. A kid does not know that he needs to learn how to do the crawl at the swimming pool. He’s incompetent at swimming, but doesn’t know about it yet. - Until …

- … he jumps into the water and experiences the second stage: conscious incompetence. He learns that he cannot do the crawl. (I learned to swim like this some months ago, using some YouTube videos as guides, and I went to the swimming pool in the evenings to not pester other swimmers with me drowning. I felt horribly, and very consciously, incompetent.)

- The third stage is conscious competence. You know how to do the crawl, but it still feels kinda unnatural, until you’ve practised long enough and are at the

- fourth stage of unconscious competence where you just jump into the pool and swim, happy as a (crawling) clam.

Tackle decision-making skills using this model. Most of your decision strategies are already at the fourth stage, so backtrack a bit to make them conscious again, then optimize, then practise.

You might want to start practising with easy contexts, e. g. at a restaurant, and then slowly expand your new skills into other contexts. Even if you’re sure that you’re the best decision-maker in the world: Look at the four strategies detailed above, then ask yourself which of these is the most outlandish, and practise this one. It never hurts to expand your skills, right?

(TBH, yes, it can hurt. But it’s the good kind of pain. Go!)